Predecessor building:

A walled courtyard, built to protect the trading place and town fair from the southern arterial road, had already been erected here prior to 1150. On the courtyard side, the oldest part of the building is a tower-like structure preserved in the cellar and ground floor levels. Today, this space can be experienced as a passage through to the courtyard and part of a retail space behind a glass wall. Until the end of the 19th century, there was a barrel vault here. A plastered vault with a pointed apex is still preserved in the cellar. Investigations carried out as part of the post-1990 renovations revealed that the existing "tower" structure was not built until around 1500, which is significant in terms of the building's history.

A striking feature of the street today, the building was built in a late Renaissance style, including the six eastern dormer windows. Groined vaults above a Tuscan column form the ceiling of the ground floor hall. During the restoration phase around 1996, later fixtures were removed from the space and it was possible to once again experience it in its original form. We see a generous vaulted arch on the north side of the hall. Above it was where the original staircase once led to the upper floor. To the west of that, the spiral staircase was accessed directly from the hall, as shown on a plan from 1893 in the Meissen city archives. This plan also reveals that there was once a wide gate on the opposite, street side – which explains the asymmetrical ceiling vault behind the present-day window front. During restoration work in the 1990s, part of the magnificent, original triangular portal crowning (tympanum) was rediscovered under plaster on the façade.

Back to the hall: a round-arched wall with Renaissance moulding completes the room – with more located (now concealed) in the east wall. Originally, there were also vaulted rooms here: a groined vault on the street side and a barrel vault on the courtyard side. This combination reveals the rooms' functions as a heated office and kitchen/heating room behind it. These vaults were demolished during the remodelling of 1939 but, with the help of building research and archival research, the design and spatial characteristics of a rich town house can be envisaged.

Renaissance structures can also be found on the first and second floors in this part of the house. The room distribution – with parlours and chambers on the street side and "serving" rooms at the rear, as well as elaborate designs with moulded stone walls and sculptural corbels, continue the style visible on the façade and in the ground floor rooms.

The façade has moulded embrasures in the upper storeys, officially attributed to the beginning of the 17th century [Gurlitt, p.196]. Two stonemason's marks were found on it, today highlighted on a black background – probably somewhat more conspicuous than originally, but still hard to spot because of their small size.

A small arch at the eastern end of the façade under the eaves cornice was built as a structural unit with the façade and the section of wall under the arch (building investigation as part of renovations in the 1990s). It can be assumed that this was an eaves alley, built over during the Renaissance era. Eaves alleys were often created between gable-fronted houses, which probably existed here before the Renaissance building.

The western part of the street-facing was significantly remodelled in the 18th century. However, it is assumed that the core of the building is much older (during renovation work in the 1990s, a three-storey quarry-stone wall was found to be the oldest component at the location of the current bend in the façade). The uniform construction of the mansard roof – with robustly dimensioned timber carefully joined in the traditional carpentry style with overlapping timber and wooden nails – unites both parts of the front house and is attributed to the 18th century.

The front house – three blocks wide (10 window openings) and two zones deep – forms one of the town's large row of town houses. The functionally and decoratively cohesive, sophisticated construction elements in the eastern part of the front house suggest a wealthy owner.

Baroque ingredients are preserved in the interior design, for example, in the finely moulded parlour ceilings on the first and second floors. The careful renovations of the 1990s took these valuable assets into account.

Further alterations were made around 1890 when the building was converted into a tax office – the lettering with the crowned Saxon crest on the main façade was reconstructed in 1998 from historical photos. In 1939, the building was again thoroughly renovated – in connection with its sale to the Stadtsparkasse Meissen savings bank. Measures such as the installation of stairs and a roof extension were carried out in a style typical of the time and executed to a high quality standard, so that they too could be retained in the most recent renovation.

The high, quarry-stone wall with its large gateway seals off the courtyard and northern perimeter of the property. It is also significant in terms of the historical layout of the town, because this is where the "holy quarter" ended – the adjoining area of the "Lorenzspital" to the north. Although their age has not yet been precisely determined, the blind arcades on the courtyard side suggest the 16th century. A wall is also shown in older depictions, such as the 1602 townscape.

Other historical features:

The building was less damaged than others during the Thirty Years' War, during the course of which the Swedish invasion on 6 and 7 June 1637 in particular caused great devastation to the town. The rear house was burnt down; "...the owner inhabits the front building..." The loss in value was recorded as 50 percent. The owner at this time was Johann Christoph Otto. "Hans Caspar von Schönberg, Cammer- und Bergrath" (chamber and mining councillor) is recorded as the owner before 1719.The house still boasted the impressive number of five beers in the 18th century and also had its own connection to the piped water system. The "...high royal treasury..." is recorded as the owner in 1833.

Development up to reunification:

In the 1980s, the ground floor was home to the Ludwig Richter House, an art gallery and dealership that mainly exhibited and sold works by regional artists and craftspeople. The upper floors housed offices of the FDJ, the GDR youth organisation. Due to its continuous use – mainly by banking and state institutions – the building remained in relatively well-kept condition until the fall of the Wall, although the building engineering was outdated and renovations were basic – without consideration for heritage value or historic architectural features. The use of the interior of the tower as a garage, and the inner courtyard as a parking, coal storage and rubbish bin area, highlighted the wear-and-tear and low appreciation of the building's historic value.

Development after reunification:

After privatisation of the property, it was modernised in 1995/1996, the great merit of which was not merely its upgrade to contemporary functional requirements. The result is a beautiful example of how inner-city spaces can be revitalised, while preserving and enhancing their historic value.

Thus, the building's historic hall can be experienced by the public – the passage through the oldest space (the tower) to the attractive inner courtyard.

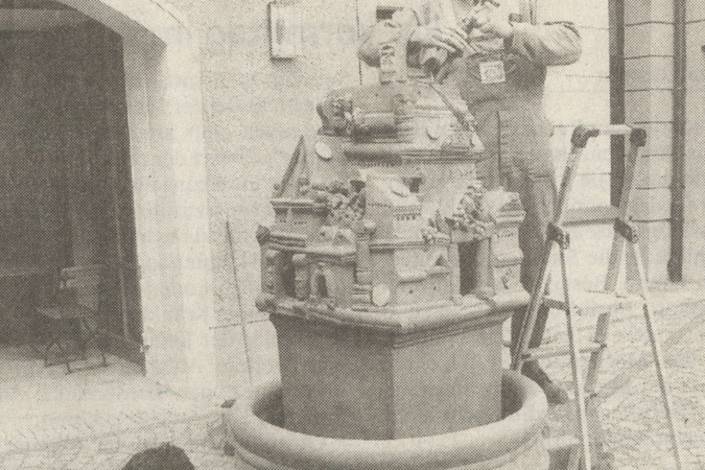

New side buildings, which conform to the style of the front building, cobblestones, and the historic courtyard wall surround the "Pfennigbrunnen" (penny fountain) created by Lothar Sell.

The living and office spaces:

Some obtrusive fixtures and fittings were removed from the historic rooms on the upper floors, and features that are both historically valuable and beautiful, such as blind arches with corbels, stuccoed ceilings, historic doors and built-in furnishings, were uncovered and preserved/refurbished. It is suspected that some details remain hidden (e.g., wall mouldings and wooden beam ceilings of the Renaissance era), left untouched because of the decorative layers over them that are also worth preserving. Functionally necessary new fixtures were carefully integrated into the historical structures as seamlessly as possible (e.g., a transparent wood-and-glass wall under the stuccoed ceiling on the second floor – as a new demarcation between hallway and living space). The tower structure in the courtyard received a new storey, with a planted roof terrace in place of its very damaged roof.