Historical heritage value & special features:

There are no remnants of a predecessor building on the property, but written sources mention two clergy houses belonging to the cathedral – dwellings for serving clergymen. The house "...at the stone steps that take one from Burggasse to the St Afra church, at the top on the corner on the right-hand side, was...rebuilt in 1509 from the ground up..." (Rüling p.172).

Urban development on the steep southern slope of the castle hill had already spread to the eastern boundary of this house, as evidenced by the original design of the east gable. To the west, however, towards the Afra church, it was free-standing, showing off the brick gable to great effect. Ornamental brick gables were no exception in the townscape of this era. Here we see a particularly elaborate one in a late Gothic style. The coloured design on the original plaster infill surfaces has not been preserved.

The late Gothic motifs are also seen on the eave-side façades, for example, the embrasures around the front door (with an arch that was later reshaped), the windows and the double-fluted brick eaves cornice. The building has a rather "closed" appearance, emphasised by the plasterwork, which was restored according to the original with quoins, plaster bands and rough-plastered surfaces (in comparison, the construction style of the Albrechtsburg castle, which was built 30 years earlier, appears open and light – much more "modern" to our eye).

Inside the house, the original layout has been largely preserved: two plank-walled parlours on the upper floors, a smoke kitchen and parts of a smoke box, the spiral stone staircase, a vaulted archive room on the ground floor, original doors, some of which are iron-bound, and the roof with its sturdy king-post construction. The wooden interior elements in particular – profiled wooden beam ceilings and board-batten walls, some of which are painted – are impressively intact. These aspects have a marked effect on the feel of the interior and, combined with the heated parlours, give us a sense of the comfortable and yet spacious living environment of the era.

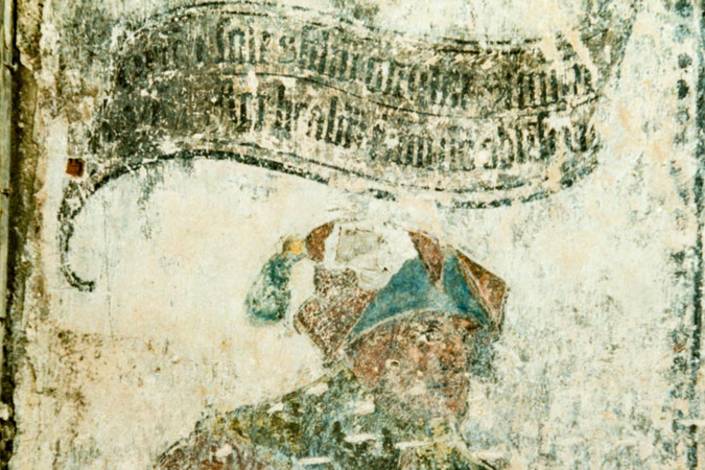

A special treasure that really completes the original structure and stands out in terms of art history is the paintings on the walls. Illusionistic architectural elements and figurative and ornamental paintings cover the stone walls in all the living spaces on the upper floors. The outstanding artistry suggests a Renaissance panel painter. It is unique in Saxony and famous among experts beyond the state borders (presumably the work of the master of the Grosshartmannsdorf altar – Preuss, 1993). In recent years, these paintings have been uncovered and carefully restored in the two plank-walled rooms.

Nikolaus Heynemann was not the only one to have the house magnificently decorated. Subsequent owners and residents also added numerous sophisticated design elements – each in the style of their era – over the original décor.

The modern-day restorations take this into account. Thus we discover several Renaissance phases, Baroque paintings, through to historicist styles from the 19th and early 20th century, which are visible in restored areas.

A half-timbered building from 1572 adjoins the main house to the north. It is one of the few surviving half-timbered houses in Meissen's Old Town and, after being rescued and restored around 2008, is once again a sight to behold. The view from the castle bridge shows the unique design of the north gable end with its round-arched windows.

The half-timbered structure houses a small vaulted room on the first floor, which borders the rocky slope to the north but is free-standing to the east and which we now call the "Brunnenstube" (well house). The well in the lower courtyard could be reached from there and water could be brought up directly to the first floor – e.g., for the nearby smoke kitchen.

The discovery of the well house and the excavation of the well shaft were possible only after the demolition of the dense structures in the courtyard at the beginning of the 1990s. Archaeological investigations during this excavation yielded ceramic vessels, porcelain tableware, porcelain pipes and many more bourgeois household items, which we otherwise only know from pictures from the time of Ludwig Richter, as the well had already been filled in and sealed over 150 years previously.

A special find was the cloister format brick with an inscription referring to 1509 as the year of construction. Hallmark stones with sun reliefs or animal paw imprints are common, but this stone is a great rarity.

Other historical features:

The oldest historical depictions of the city (Hiob Magdeburg 1558, townscape of 1601) depict the building with its high, pinnacled gables, which were rebuilt in 1973 and after 1990 and are a special feature of the townscape. M. Nicolaus Heynemann was the owner and builder of the house, named not only as a priest, but also as episcopal official (representative of the bishop as a member of his ecclesiastical court), as well as papal and imperial notary from as early as 1502. He lived in this house until his death in 1544. As early as 1513, it was also recorded as a clergy house associated with the cathedral ("vicaria divisionis Apostolorum" – Rüling p.172), jointly bequeathed by the owner and the town council ".... in its entirety ..." that year.[ Note: this means there was already a connection between the town council and the house in the 16th century]

Important people in the history of Meissen have lived here over the centuries:

After 1544, the (episcopal?) bailiff Hieronymus Ziegler; late 19th century, photographer Germanus Koczyk, who ran one of the oldest photographic studios in Meissen and built a studio in the Swiss chalet style on the terrace at the south of the main house, which is now open again; early 20th century, Oskar Burkhardt, porcelain maker at the Meissen manufactory and well-known local painter, whose memoirs were published and some of whose texts and paintings were dedicated to the ageing house.

Development up to reunification:

In the early the 20th century, the distinctive brick gables above the roof were dismantled. Around 1973, the brick gable on the town side was rebuilt – instigated and supervised by the IfD (the GDR Institute for the Preservation of Historical Monuments). Until the 1980s, parts of the house were still inhabited. By 1986, there were increasing signs of dilapidation. This became externally obvious with the installation of wooden eave scaffolding, which caught falling roof tiles. There were many such safeguarding structures in the townscape and they multiplied drastically in the 1980s – including the houses on the slopes of the castle hill. This was summed up memorably by the poster "Visit Meissen while it is still standing", created around 1989.

In 1983, students from the Technical University of Dresden carried out a dimensional survey of the existing buildings (such surveys had been conducted increasingly since the 1960s in Meissen – and in many other GDR towns rich in heritage buildings, mostly in connection with historical building research. This continuing, praiseworthy work can be seen as a broad documentation of the historical building stock, and has been gladly taken up and used to inform modernisation planning by building and project planning institutions).

Plans to modernise it as a residential building did not advance past the initial stages. Even plans to preserve it (1988, VEB Denkmalpflege Dresden) remained on paper.

The architectonic value of the house was enhanced by the discovery of the unique wall paintings. From the mid-1980s onwards, citizens of the town worked together, employing simple means to carry out urgent measures in attempts to halt the building's progressive decay.

Development after reunification:

After intensive efforts by monument conservationists and the town, the roof and west gable were repaired in 1994/95. Recognising the building's great value in terms of architectural and art history, the town acquired the building at the turn of the millennium. A non-profit association – the "Rettet Meissen Jetzt" (save Meissen now) curatorium – has been organising public access and step-by-step, careful structural repairs and restoration work since 2000, with the support of the Deutsche Stiftung Denkmalschutz (German Foundation for Monument Protection), the Ostdeutsche Sparkassenstiftung (East German Sparkasse Foundation), Sparkasse Meissen, urban development funds, as well as its own funds generated by numerous ongoing donations from friends of the curatorium and the house.

Essentially, the building has been saved – but there is still much to be done by the association and the town to fully open up this treasure trove to the public. It can still be further revived as an attraction the people of Meissen and Saxony can be proud of.