Due to its half-timbered construction, the building now stands as a heritage gem in Meissen's Old Town. In terms of urban topography, it belongs to the formerly independent "free" legal area. This is where buildings belonging to the cathedral chapter and freeholds of the Meissen land-owning aristocracy were located. The house itself has medieval construction elements in the surviving structure (cellar). Medieval documentation of the building remains subject to further research, as numerous references in the sources have not yet been clearly assigned. It was not until 1 January 1847 that the privileges of "free" citizens were abolished. These consisted of a separate jurisdiction, exemption from all municipal taxes and burdens, and the prohibition of crafts and commercial activities. The assignment of houses to the municipal legal area and to the town administration can also be read from the property's land register entry. The "Urbar" – the municipal land register – had been maintained by the town clerk since 1719. There are entries for Schlossberg 3 from 1840 onwards. The people who used the building over the centuries have so far only been partially identified (from the 19th century onwards). One possibility is that it was a residence for builders, who were needed by the cathedral chapter for its economic operations and also by the freeholders.

The building is one of the few surviving examples of half-timbered construction in Meissen's Old Town. The situation in Meissen was markedly different in the 16th century, when half-timbered construction was the predominant style. The "Swedish fire" in 1637 during the Thirty Years' War and the extensive building losses associated with it forced the development of stone construction. The "Willkühr" (the municipal building regulations from 1585) promoted the subsequent stone construction.

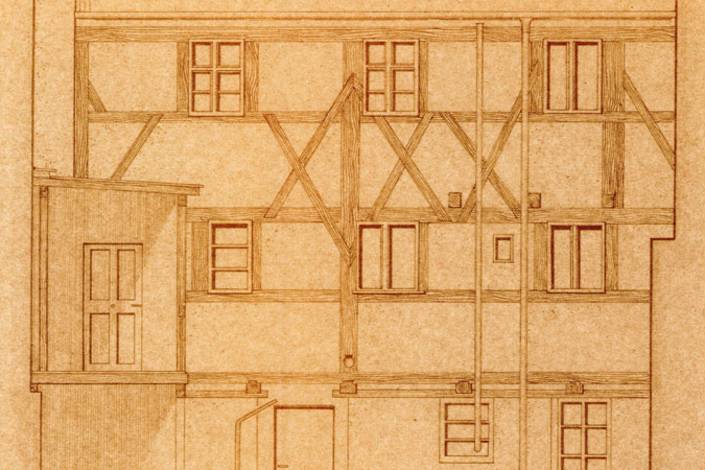

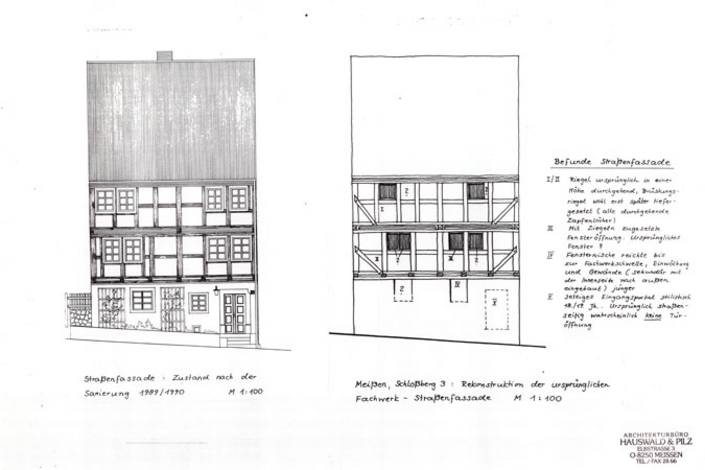

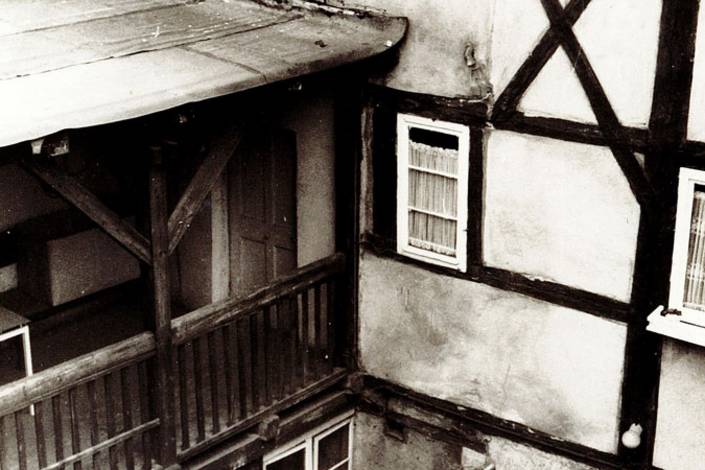

The timbered building at Schlossberg 3 has been dated to 1575 on the basis of dendrochronology. The east and west gables were originally free-standing. The west gable on the uphill side, designed to be visible, is typical of the era and was built over in the course of the Baroque reconstruction of the Löthainer Hof (Schlossberg 2) in the first half of the 18th century. The eastern gable on the downhill side was shored up with the construction of the residential building at Schlossberg 4. It is not yet clear when a building was first erected here. The plot of land (1830 plan, p. 14) originally belonged to the procurator, as did Schlossberg 3 (1830 plan, p. 13). The properties that the territorial lord had acquired from the Bishopric in the course of secularisation in the 15th century were brought together under the procuratorate. The surviving historicist building was erected in 1866. The beginnings of the building stock date back to the 13th century. The southern cellar barrel vault was built during this period with strong loamy mortar. This basement level was originally at ground level and not recessed. The entrance was probably on the eastern side. The ground floor consists of solid mixed masonry, 90cm thick, tapering towards the top. The simple entrance portal with the classicist door was built in the first half of the 19th century. Access to the ground floor was originally via the two Renaissance portals on the south side. The smoke kitchen was installed after the 1575 reconstruction. The smoke was apparently discharged into the main storeys, via a chimney, because the roof truss is blackened. Despite the slightly different designs, the uniform-looking half-timbered upper storeys belong to the 1575 construction phase. The storeys are jettied on the street-facing side. The second storey slightly overhangs the first storey. The beams inserted between the top and bottom wall plates are profiled with fillets and beads in a "Schiffskehlprofil" (ship fillet profile). The courtyard side used a post-and-beam construction. Vertical beams run across two storeys at the gable ends and in the middle. The pergola on the courtyard side, originally required for covered access to the toilets, was rebuilt at the end of the 19th century due to dilapidation. The roof structure is a two-bay, "Spitzsäulen" (peak column) construction. Pointed columns stand at the gables and the middle of the truss. The rafters and top beams are cross-lapped. The pointed columns are double-interlocked lengthwise and braced with cross-lapped, intersecting diagonal struts. The roof truss dates from the 1575 construction phase.

Among the interior details that are important from the point of view of heritage conservation are: the remains of the smoke kitchen from 1575; the beamed ceilings on the ground floor (here only beams visible, panels infilled with loam), first floor and second floor; the block stepped staircase to the first and second floors; as well as numerous historic doors with fittings and locks from the 18th and 19th centuries. The façade was repainted according to evidence found: very dark wood (almost black), white infill, and black stipple painting.

The building survived a period of critical endangerment in the GDR era. The house was occupied until the end of the 1970s. At that time, it was bought by a young family who intended to live in it. This failed due to personal problems. The family gifted the building to the municipal housing administration. In 1982, Kreisbau Meissen began to draw up project documentation for the building due to its endangerment. The plan was to develop the building into a block of flats. Those in charge quickly realised that because of special structural features – there were numerous deviations from the applicable TGL standards (equivalent to today's DIN standards) – the project could not be implemented. So, the house stood empty until 1988. That year, it was bought by the family of an architect from Meissen, and they began the urgently needed renovations. The building was unquestionably wonderfully suited for use as a single-family dwelling. And so the building's valuable interior assets were not put up for disposal. The building's critically endangered phase was over by the transitional year of 1989. The family was able to complete the building renovations in 1991.

In retrospect, it is a wonder that the use of the house by multiple tenants functioned for centuries. In 1876, for example, there were twelve residents divided into five rental parties. What else can be inferred from this? The capacity for buildings to be transformed without endangering elements of important heritage value.